The government has formally announced that restaurants with more than 250 employees are now be required to display the calorie content of each meal on their menu in an attempt to tackle obesity.

As with most government legislation, this has been met with a dichotomy of views, but arguably a flare-up of passion too.

For us at Fresh Fitness Food, we believe in sustainable nutrition, and nutritional education (which is why we aim to provide you with so many blog posts and webinars!).

Because of this, we found ourselves to be slightly disappointed in this new legislation, which may be surprising coming from a company that provides bespoke nutrition to thousands on a daily basis. But please, hear us out.

To start with, what is the actual legislation that is being implemented?

If you haven’t heard, from April 2022, large businesses (classified as those with 250+ employees) will be required to display calorie information on menus and food labels. This is allegedly to “help the public make healthier choices when eating out” (Gov.uk, 2021).

The regulations will impact any business that sells food and/or drink, including but not limited to cafes, restaurants and takeaways, who will need to provide the calorie information of non-prepacked food and soft drinks, at the point of choice.

As mentioned, this will impact cafes, restaurants and takeaways, meaning that calorie information will be displayed on physical and online menus, but what is not quite so obvious is that this will also be a requirement for food delivery platforms (such as Deliveroo, UberEats and Just Eat) as well (Gov.uk, 2021).

The government has chosen to highlight the way that COVID-19 has impacted obesity, both health-wise and economically.

Health-wise, they have emphasised that almost two-thirds of adults in England are overweight or obese, and 1 in 3 children leave primary school overweight or obese.

A 2015 study by Adams et al determined that those of a higher socio-economic position are significantly more likely to dine out one or more times per week.

In 2016, Booth, Charlton and Gulliford found that in a sample of 26,898 Brits, socioeconomic inequality was a strong factor in determining obesity risk, in that those considered to be of lower socioeconomic status had a much higher association with obesity (Booth, Charton and Gulliford, 2016). You can read more about how the cost of food affects diet here.

Therefore, by method of deduction, those that are frequently eating out are much less likely to be at risk of obesity than those who are not eating out.

Statistically, those that are obese and eating out are less likely to be doing so frequently. Therefore, if a meal out is seen as a special occasion or one-off, will displaying the calories have any impact?

Not only this but solely displaying calorie content and no other nutritional information (such as macronutrients) enforces the rhetoric that nutrition is solely about calories – something that nutritionists and health care professionals actively try to educate against.

Without the nutritional information to accompany them, calories have much less meaning.

Let’s take a look from a different perspective…

There are two political candidates running in an election. Candidate A wants to increase taxes, whereas candidate B wants to decrease them. With this information alone, you would likely vote for candidate B over candidate A.

You later find out that candidate A only wants to increase taxes by 1%, and will use that increase solely to increase funding for the NHS. Candidate B, whilst pledging to decrease taxes, wants to privatise the NHS instead. Upon learning more information about each candidate, and the context of the information initially given, it makes it easier to make an informed decision on what benefits you best.

Although a potentially far-fetched example, it illustrates how individuals need contextualised information before they make a decision. Just because an item is “low calorie”, it does not make it healthy – a small, beer-battered cod and a standard salmon fillet each come to approximately 300 kcal per serving. Both are a source of fat and protein. However, without being able to see that the salmon is lower in saturated fats while maintaining high protein, the decision is much more tricky.

The British public needs nutritional education so that they grow up with knowledge of how to eat a healthy diet and properly assess nutritional labels, and not solely base their choices on calories.

The majority of restaurants that these regulations will affect already have the nutritional information for their menus available online or in-store (think: McDonald’s, Nando’s, Wagamama’s, Itsu), and have done for a period of years, yet obesity is still on the rise. If consumers want the information, for the most part, it is already available.

What does the data show?

Generally, not a lot. Currently, there is no sufficient evidence to show that adding calorie counts to menus shows a sustained decrease in calorie consumption over time, nor that it leads to a reduction in weight.

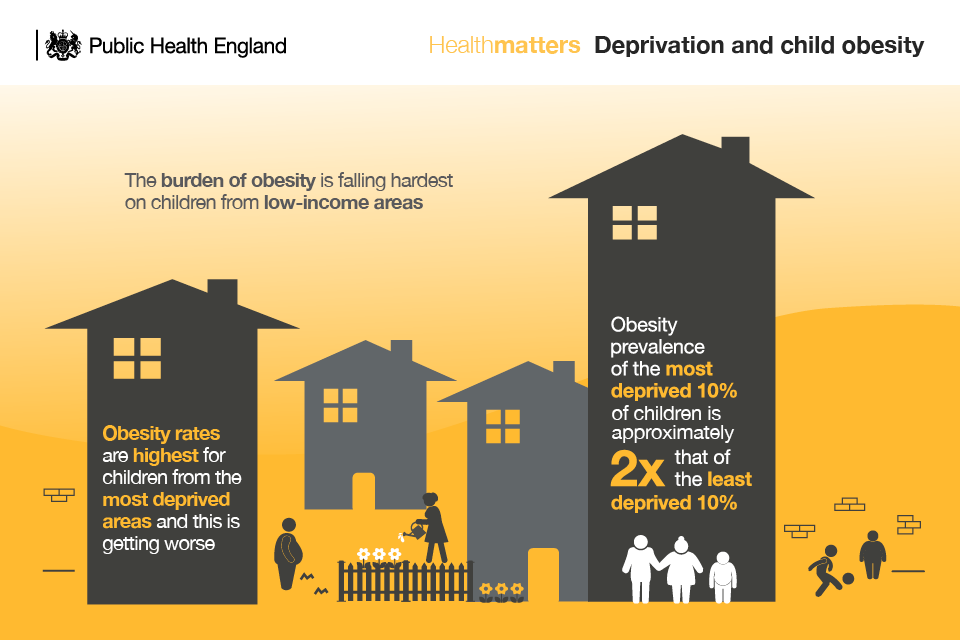

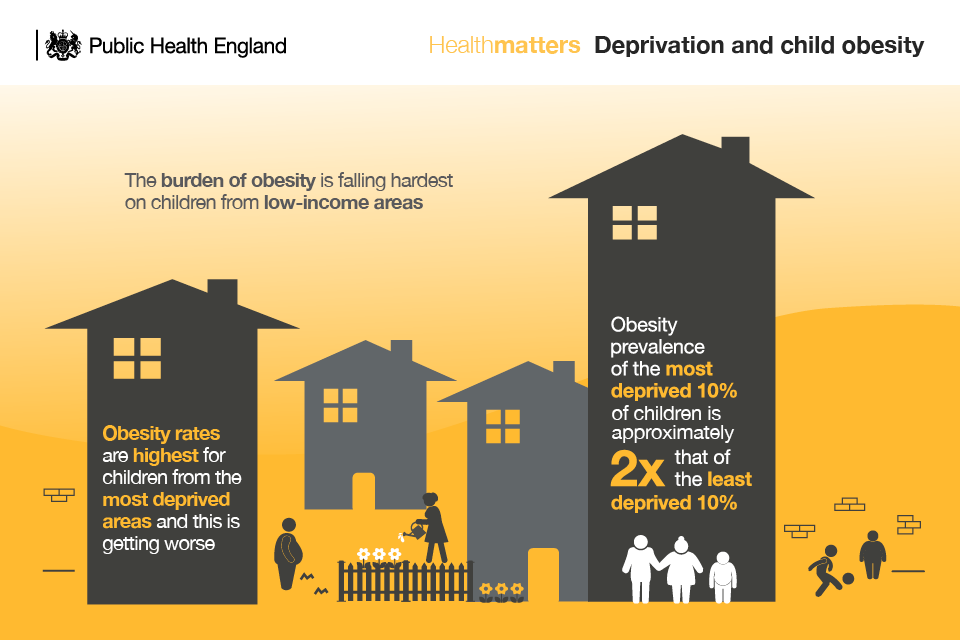

In 2017, Public Health England created the following infographic, in combination with data showing a strong positive correlation between deprivation and the number of fast-food outlets per 100’000 people (available here).

This, therefore, shows that the government are aware that obesity is a more prevalent issue in those who are more deprived, so is attempting to tackle obesity through adjustments to dining out that logical?

What about those who are more sensitive to calorie displays?

The government has set a provision that allows businesses to provide a menu without calorie information, but have specified that this is only available at the “express request of the customer”. For those who already experience heightened anxiety over dining out (for example, those with eating disorders), having to single themselves out and ask for a different menu can increase anxiety further.

Furthermore, many with eating disorders/disordered eating behaviours have taken to social media to express that they will not be eating out if the new regulations are implemented due to the increased stress and potential disruption to their recovery.

In December 2020, the NHS published their Health Survey for England 2019, which found that 16% of those ages 16 and over screened positive for a possible eating disorder (NHS, 2020).

NHS mental health services are already underfunded, which puts strain on charities such as Beat, who help support those affected by eating disorders.

In April 2020, BBC Horizon launched The Restaurant That Burns Off Calories – a TV series where a restaurant doubled as a gym with individuals on exercise bikes, treadmills and rowing machines, who had to burn off every single calorie ordered and consumed by the diners in the restaurant.

The airing of the first episode alone resulted in a 30% increase in calls to Beat, who were already facing an influx in those needing support as a result of lockdown (Birmingham Mail, 2020). The charity has expressed major concern about the new regulations and their capacity to help those that need it and actioned a petition to oppose the changes.

It is also extremely important to note here that those with eating disorders are not exclusively thin or emaciated. Eating disorders can affect anyone of any age, background or size (check our EDAW post here for more information and statistics on eating disorders).

Individuals with binge eating disorder are 3-6 times more likely to be considered obese than those without an eating disorder, with high associated with childhood obesity as well (McCuen-Wurst, Ruggieri and Allison, 2017), meaning the concerns are far more deep-rooted than the government is implying.

Arguably most importantly, binge eating is more prevalent among those attempting to lose weight, compared to those who are not, which, when simplified, means that the calorie displays with either be ignored by those with obesity entirely or may enable eating disorder behaviours in those trying to lose weight.

Furthermore, having calories listed on menus may result in parties engaging in conversation about calories and “healthy” food, which may not be constructive to those who would rather not engage in that sort of behaviour.

The financial aspect

Finally, the financial side of the regulations needs to be considered.

The hospitality industry lost around £220m of sales EVERY DAY from April 2020 to March 2021 – a total estimated of around £80.3 billion in the same period.

The amount that the regulations will cost restaurants is estimated to total as much as £40’000 per menu run (Big Hospitality, 2021), which could significantly add to the already drastic losses restaurants have faced due to Covid, particularly when considering that some may stop eating out altogether if the regulations go as planned.

As it stands, there is currently no succinct or substantial evidence from previous studies to indicate that adding calorie counts to menus will reduce obesity rates in the UK.

Obesity rates are twice as high in the most deprived areas, compared with the least deprived areas, in both children and adult populations. As mentioned, many of the restaurants that those considered obese have the easiest access to, already display the nutritional information for their meals online (and some even on ordering menus themselves, such as McDonald’s).

Statistics show that those considered obese are less likely to be dining out frequently, and if they do, they are likely to be eating at an establishment that already has readily available nutritional information.

While the regulations may result in revisions to the dishes themselves on a menu, hopefully with an increase in “healthy” options available, it seems that the regulations, as they stand, will not be largely effective in targeting the required demographic, are at risk of damaging (or further damaging) individuals relationships’ with food, and will add significant costs to an industry that has faced almost 13 times more loss in the last year than obesity and overweight costs the NHS in a year (Gov.uk, 2021)(Big Hospitality, 2021).

For real change to be made, healthy food needs to be made more accessible to everyone.

Fresh Fitness Food provides personalised meal plans delivered straight to your door, ensuring not only that you have the nutrients you need to manage your stress levels, but also that you have the time usually spent shopping, cooking and washing up, to engage in your favourite stress-reducing activity. To discuss which nutrition plan is right for you, book a call with our in-house nutrition team here.

Order today and start smashing your goals with personalised nutrition!

Get £50 off a 5-day trial with code: BLOG50. Start your trial here

References

Adams, J., Goffe, L., Adamson, A., Halligan, J., O’Brien, N., Purves, R., Stead, M., Stocken, D. and White, M., 2015. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of cooking skills in UK adults: cross-sectional analysis of data from the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 12(1).

Birmingham Mail, 2020. Fred Sirieix’s BBC show Restaurant That Burns off Calories sparks fury over ‘encouraging eating disorders’. <https://www.birminghammail.co.uk/news/showbiz-tv/fred-sirieixs-bbc-show-restaurant-18122548> [Accessed on 2 June 2021]

Big Hospitality. 2021. Mandatory calorie labelling for out-of-home food businesses employing more than 250 confirmed. [online] bighospitality.co.uk. Available at: <https://www.bighospitality.co.uk/Article/2020/07/27/Mandatory-calorie-labelling-become-compulsory-for-restaurants-employing-over-250> [Accessed 2 June 2021].

Booth, H., Charlton, J. and Gulliford, M., 2017. Socioeconomic inequality in morbid obesity with body mass index more than 40 kg/m2 in the United States and England. SSM – Population Health, 3, pp.172-178.

Gov.uk, 2021. Calorie labelling on menus to be introduced in cafes, restaurants and takeaways. Available at <https://www.gov.uk/government/news/calorie-labelling-on-menus-to-be-introduced-in-cafes-restaurants-and-takeaways.> [Accessed 2 June 2021]

McCuen-Wurst, C., Ruggieri, M. and Allison, K., 2017. Disordered eating and obesity: associations between binge-eating disorder, night-eating syndrome, and weight-related comorbidities. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1411(1), pp.96-105.

NHS, 2020. Health Survey for England 2019 [NS]. Available at: <https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/2019> [Accessed 2 June 2021]

NHS, 2020. Statistics on Obesity, Physical Activity and Diet, England, 2020. Available at: <https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/statistics-on-obesity-physical-activity-and-diet/england-2020> [Accessed 2 June 2021]

ONS, 2020. Monthly gross domestic product by gross value added, 11 September 2020. Series: ECYT, ECYJ, ECYH, ECYD, ECY9, ECY6

Public Health England, 2017. Health matters: obesity and the food environment. Available at: <https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-obesity-and-the-food-environment/health-matters-obesity-and-the-food-environment–2> [Accessed 2 June 2021]